For many years, I longed only for the beach.

But when I finally moved just an hour-and-a-half from the island, it still took several months before I even made it down there (for work, no less). I had been away from the beach for a long time.

In those days, I was still working in a cancer research laboratory, in the middle of the biggest city I’d ever seen. You see, I really did grow up in the woods, much like the little mountain boy I wrote about in the crayoned books on my homepage and my other 3rd person scholarly analysis of The strangest snowy day. (I also dramatically read through the whole thing bedtime-story style last year on TikTok)

But, I missed the ocean — or something like it — most of all.

Early one Thursday morning, I drove toward the island, and this song was playing on my phone through the aux cable poking out of the cassette adapter (it was 2015 after all).

Without listening too hard, you can tell the exact spot where my little old car crested me, crying over the apex of the long, sunny causeway bridge over the water. In tears, I silenced the radio and just watched the water glimmering. It’s a very long bridge, and a part of me was coming home.

It was cold, November, because it was cheaper for the college that time of year. I still swam at night, though, having never been stung by a jelly fish still, back then.

A couple of my co-workers left the bar with me that first night we were there, crossed the street and took off their shoes, too, and wondered how long anyone could really enjoy themselves in that scary black water without freezing. I was grinning like a kid when I finally reappeared from the surf a while later, chattering and jumpy as I briskly and violently dried myself off.

Jessi said her little boys also liked chasing the piping plovers, hunting in little groups at night, but they were six and nine.

Paola said her family liked to drive down at sunset when the tourists were packing up and the parking police mostly went off-duty. She and her mom and her sister would sit under the blankets, laugh, eat, sleep for a while in the sand. Her dad would just walk up and down the beach most of the night, take a nap, walk some more, roll up his jeans and look for shells. Then they would all go home in the morning after the sunrise, gritty and wind-blown, sleeping in the car on the way back to town.

I moved a couple times, away, around, then farther away from my island again, and it wasn’t even my island yet until a few years later. Right after a Corona-era breakup, the end of an engagement, stuck living in a hotel for over a week, living in yet another new city where I didn’t know anyone else, alone, frozen, stuck, eating hotel omelettes in the hotel laundromat.

I just left, and I went straight back down to my island, across the same long bridge, humming my same old sadly triumphant Rachmaninov moment from six years earlier, and (having nothing much to speak of that didn’t fit in two carloads) I rented a furnished apartment for a month, one month that perpetually reproduced itself into two years, and then still kept going. Kept ticking away as if it might never stop.

It was a few minutes bike ride, a little longer on foot, but I am confident I easily went to the beach 800 times, wandering like Paola’s dad, or biking through the wet sand, until I had eventually stopped picking up shells and let the piping plovers and pelicans be, like a ten-year-old waiting to turn grandpa.

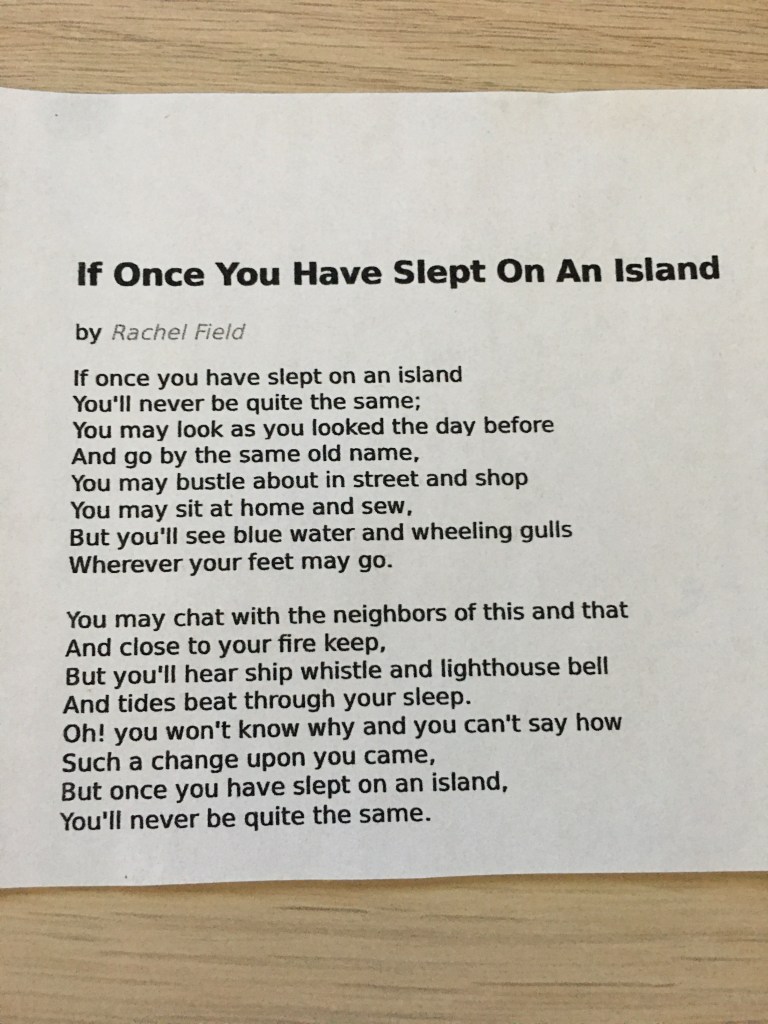

When I had first started living on the island, my island, with no plans to leave, my mom sent me a poem and a dish towel with a starfish on it (not pictured).

For my yet-to-occur, future over-the-shoulder glances, past, past-fawning. Eight hundred beaches change you, but probably in the same way that 900 beaches would. I had stopped taking sunset pictures. I started to always leave my phone at home so I could just swim (not pictured).

People who die and come back sometimes say they remembered every single moment of their entire life in one instant. Again a second flash, and then they felt everyone else’s feelings who were affected in each and every one of those life moments, from start to finish. Strange to have that unfathomable, built-in capability tucked away behind this obviously rather slow and cumbersome person, limited, obtuse, confused, obscured.

Nothing is really in the past, eventually.

Such a change upon you came.

You won’t know why and you can’t say how

You won’t live here forever, I thought, after the first year had gone by.

You might get stuck here forever.

Looking back, it was really very sandy all the time. But that felt pretty nice, too. It wasn’t ever going to be a good time in my life, so I went down there to wait it out. I worked, biked, walked, stared, baked bread, wrote a little sometimes, and otherwise did generally a whole lot of nothing of any great consequence. I didn’t know if it was working.

Somewhere in that lot of nothing, such a change upon you comes.

“Wiayell, ah remember when ah first moved down here, I just sleyept and sleyept. It’s just heveh or somethin’, the ayeir’s differnt,” my first landlady recounted, “Yer on ahhland tiiim, neyoww, which is the wai-fai paiyss werd, bah the waiiy. One word, alll lowercase, islandtime…Come on, come on Hank, HAYYYYNK! Momma’s gotta take ya’ to get cher haircut, it’s Wen’sdy.”

“You’re alone on the surface of the moon,” my friend told me that first cold beach February.

Leave a comment